Tuesday, February 28, 2006

Monday, February 27, 2006

photos of the civil rights movement rediscovered

Here's the story in the Washington Post. Click on the link to the photos themselves, if you have a chance.

sms

Thursday, February 23, 2006

Jazz before 1930

jazz was much closer to the blues, on the one hand, and less "free" than later jazz,

which is still evolving. So have a listen!

http://www.redhotjazz.com/index.htm

Susan

Prof. Heberle on THAT poem

I was...

I don't know the poem, but she seems to me an apparition--a slightlybedraggled Muse (she gets less attractive in every war) who allows thewar writer to bring something "positive" out of the experience--his lifeand his poetry.That's my guess, for what it's worth. She's always near a bridge maybebecause she's come from somewhere outside the war herself or because she'salways keeping the surviving writer alive when he thinks or thinks he seessomething other than the war?Mark

Morrison... Yeah.

One thing I found interesting was the way the narrartor describes Joe and Violet's marraiage from Joe's point of view; their initial meeting in Virginia specifically.

"They were drawn together because they had been put together, and all they decided for themselves was where and when to meet at night." It's as if their relationship involved no sense of personal freedom. Like they were together because the cosmos had arbitrarily decided it so.

It's interesting to remember that their romance began in the countryside of a country state. And when contrasted with the way the characters feel about the city and the way the narrator describes the energy and essence of life there, you see the difference between a lifestyle which was ordinary and predictible, with one in which any and all things are possible "Do what you please in the city, it is there to back and frame you no matter what you do." The city is pure individual freedom. Everything can be. "And what goes on on its blocks and lots and side streets is anything the strong can think of and the weak admire." The city is a place where everything is yours for the taking, if you've got the ganas. Again, pure an unadulterated freedom, well maybe not unadulterated in the case of Joe.

Jazz is all about that freedom. Within the structure of a composition, jazz more so than any other type of music allows for that individual, crazy, whatever the fuck I want attitude to take flight, to make cliche reference to the story. The drummer will take a solo, the trumept player will scream out high pitched notes that sound more like a catfight than anything resembling music. Jazz is all that insanity that takes place within structure. When some people describe jazz they'll sometimes say that everything happens between the notes. Between the notes, people act in ways, previously unimaginable: they cry harder, they laugh louder, they love like never before, and unlike anything seen before in a movie or read about in a book.

I'm definitely over-dramatizing everything, but maybe not.

The narration as well enjoys a roaming sense of freedom. Who is he? she? and where and how does he have so much insight. Morrison is a badass. Winphrey Idol of worship or not, she's a badass.

She makes me want to live like jazz. Eventhough I'm just a tool of a college kid living more in my words than anything else. God!!!

Jazz seems cool and I hate blogs

But anyways, the Jazz book we are reading now by Toni Morrison seems pretty interesting. I personally don't know too much about Jazz but I am looking forward to the presentation on Jazz. When I was reading the book it kind of reminded me of another book we read when I was a junior in high school called "The gtreat Gatsby". I'm not entirely sure because I don't remember what happened in that book anymore, but I think it was during the Jazz Age and had to do with a love story also. But it was about rich white people. Maybe I'll read that book again just to refresh my memory. But yeah, the book is pretty good so far and I like it.

This Young Good god Young Girl Who Both Blesses His Life And Makes Him Wish He Had Never Been Born.

My opinion may change—and I certainly hope that it will—but the first fifty-one pages can be summed up like this (Sau Notes!):

- Violet adores birds. They have no children together, despite the fact that they have been “together” for over two decades.

- Joe had an affair with a 18-year-old named Dorcas (yes, that’s a female name in Morrison’s crazy crazy world)

- Joe kills Dorcas because he loves her. Violet—playing the stereotypical role of the crazy bird lady—tries to cut open Dorcas’ face at the funeral. Despite the fact that it makes no sense since Dorcas is um, dead.

- Joe is an Avon man. Or in this case, a Cleopatra man. Violet works as a freelance hairstylist, which is to say that she is largely unemployed.

- Violet strikes up an odd friendship with Malvonne, who is Dorcas’ guardian and aunt.

- There is some mention of a threesome.

Oh, the only music of jazz scene or music is actually about blues. And any good pretentious jazz aficionado will tell you that blues is something separate from their beloved John Coltrane.

Again, I sincerely hope that further reading of Jazz will help me belove the novel further. But for the time being, please enjoy the summary for those of y’all who have yet to read the first fifty-one pages.

I need to illegally download some Jazz

I feel so relieved reading this novel. After Dispatches, it is a breath of fresh air. It really is. Yes, it does jump around a bit, but I seem to be able to follow it much better. I don't get lost and confused and have to try to force (and fail) to see a central plot.

What is with the STH at the beginning? Is it explained later on? I have not reached the 51 page mark yet (I will tonight) but I don't see what it means at all. Does it mean "Something?" I've seen some people on the internet substitute sth for something, but I don't know if Toni Morrison is a big internet geek or sth...

I really like her sense of humor. I like this line in particular: "Some old people who didn't slap the children for being slappable; who saved that strength in case it was needed for something important."

That's just FUNNY. I've know some very "slappable" children. Damned if they weren't always the children with parents that DIDN'T slap em. lol.

I also really love how the husband looks at the photo because it doesn't have an accusing stare like his wife's. This stuff is gold. :)

Very interesting how the past actions are being revealed in the story. I'm gonna go read some more and sleep.

Laters

Josh

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Sunday, February 19, 2006

chronology for Toni Morrison's JAZZ and more TM links!

http://www.vanderbilt.edu/AnS/english/Clayton/234jazz.htm

When you read the author's forward, you will understand why she chose to write the book as she did.

Morrison knows her history, her culture, her music. This book is a great launch pad into early 20th century American history. A very few links follow. Track some down for yourselves.

For the East St. Louis riots:

http://www.exodusnews.com/HISTORY/History010.htm

My late father was sent south from Michigan after he was drafted into the army for WWII. He said he wept as the bus went through east St. Louis. Not a happy place.

To find out more about the Great Migration of black Americans from the south to the north, check here:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/flood/peopleevents/e_sharecroppers.html

And here are some music links:

Race records (African American music on records):

http://www.pbs.org/jazz/exchange/exchange_race_records.htm

Okeh records, mentioned more than once in the book:

http://www.geocities.com/SunsetStrip/Club/4041/

Look for Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington, among other musicians of the time.

aloha, sms

Saturday, February 18, 2006

Komunyakaa and music

http://www.poets.org/viewmedia.php/prmMID/5828

aloha, sms

Euphemisms

http://mediamatters.org/items/200602170013

Friday, February 17, 2006

Danny GLover looks a little like Komunyakaa

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Small Group Kine

Holy Crap

Last time we talked about the ways in which Dispatches and Dien Cai Dau depict the war. Dien Cai Dau seems to show compassion in a few of the poems. I think it was "We Never Know" in which the narrator describes the dead soldier clutching a picture of his girlfriend/wife and then how he turns him over so he is not kissing the ground. I think that those cases of war are few and far between and for most, the war does not draw out compassion, but rather the worst in us. That is why I am posting a video of some British soldiers beating up some Iraqis. I guess this video has been all over the news but I haven't seen it so maybe everyone else hasn't either. Anyway the point of me posting this is to not see some British soldiers beating up unarmed civilians but rather to hear the wickedness in the voice of the person who is taping the beatings. He doesn't start saying anything until the beating starts and it's very chilling. From Dispatches there were stories about men smiling after shooting Vietcong and well I think this video is a modern day version of that.

http://media1.break.com/dnet/media/content/britishiraq12.wmv

...and in the other corner...komunyakaa

I like how the narrator of most of yusef's poems brings to play the humanistic side of the enemy. The VC exist in a form much greater than bodies, targets, etc. I did like, though, how Herr admitted to the fact that his account would be rather biased. He didn't bother being fluffy about things. In the words of Sau...he was more like "Dude, check it...here's how it was...do what you will with it."

Although I agree with both sides, showing reality in all its aspects, I must say that yusef's work...in a literary perspective is much simpler to read (for some reason, i cant stress this any more).

I suppose I welcome the poems a lot more, not just in respects of the structure, but also because elements within each piece is described much more closely to the stories that I read in my spare time - there's description of place, feelings, imagery really helps me. When i read i must admit to favoring more showing and less telling - there's a english major cliche for you!

I admire how Yusef tends to take something otherwise lifeless, and meld it with nature. I could be reading into things far to much, but a poem that really grabbed my attention was on page 11 "A Greeness Taller Than Gods."

When I read the poem two lines jumped out

"a green snake starts again through deep branches." This could be read just as is, but I saw the snake as the Viet Cong, and the shape of a snake made me picture the tunnels that they used to travel below ground.

"Spiders men webs we marched into" remined me of how in Operation Rolling Thunder (the GRADUAL attack on bridges, bases, etc) the enemy tended to adapt, and make up for the damage done. The action of a spider mending a web was much more to me than an act of nature. Instead this highlighted Yusef's tendency to creat a world that becomes very nature bound. I love it how he does this...then again I could be way in left field, and it wouldn't be the last time this has happened.

Why I always hated my name...

For the most part, I don't like comparing non-fiction/fictionalized journalism/journalism (or whatever it was) with poetry because people choose to write in different forms for very specific reasons--but I do choose favorites. And I choose poetry.

I appreciate the shorter more power packed poetry of Komunyakaa to the, at times, long-winded descriptions and military jargon of Herr. With Komunyakaa you are garaunteed a "aaahhhh" moment with every poem (or sometimes a "WTF?" moment for the more confusing ones). While with Herr it was more skimming, as ANdy mentioned, for the good parts.

Oh yeah, like Sau said, "Sappers" is my favorite poem. My little annotation on the bottom says, "almost intimate." And the more I read it, the more and more intimate it becomes. I think that says a lot for a poem about people trying to kill each other.

amlit338

Muy Loco. Yo soy yo, Don Quixote, el hombre de la Mancha!

For some reason, I find "Dien Cai Dau" to be a much more interesting read than "Dispatches." You had me at "We tied branches to our helmets," Komy. In "Dispatches" it seemed as if we were seeing everything from too subjective of a viewpoint. Everything was stated and written in a manner to convey the facts, even breathtakingly boring ones about troop movements and all that rot. In "Dien Cai Dua" it is more personal. There is a sense that you are in the thick of it, standing next to the author, looking down his scope, smearing mud on your face, putting branches on your own helmet, shooting at people, fragging officers, and even sitting on stools. It grabs at you and brings you into the story. Yes, they are poems. It's not really a "story" to most people, but I see all of his little poems as really, really, really, short stories. Some are simple stories, like "To Have Danced With Death," which is nothing more than what seems to be the author watching a man enter a room, shifting around in his pockets, and being snubbed by the people in the room. Others, like "One Legged Stool," are confusing rants that could take minutes to decipher all of what is going on.

Wednesday, February 15, 2006

Women Generals of the Yang Family

-Ciao

-Joshua

Edit: You give extra credit for seeing plays? Dis one count? :)

james brown

alas, my cd collection doesn't include any James Brown. So here are a few itty bitty samples for you:

http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B000001DUP/102-0862766-4896161?v=glance&n=5174

enjoy.

sms

...blameless as a blackbird in Hue...

Komunyakaa sets the pace of his collection of poems with “Camouflaging the Chimera.” Komunyakaa writes about how he and his comrades waited in the forestry of Vietnam. And how the waiting creates the anxiety of an attack. As Komunyakaa writes, “a world revolved under each man’s eyelid,” there is a sense of the premature aging that took place among soldiers during the Vietnam War.

In “Tunnels,” Komunyakaa talks about the suicide that it is to be a tunnel rat. Following “Tunnels” is the poem “Somewhere Near Phu Bai,” where Komunyakaa contemplates suicide. But his exhaustion becomes too daunting and Komunyakaa ends up “counting sheep before I know it.”

Dien Cai Dau is vocalized in the poem “Starlight Scope Myopia.” Komunyakaa views the enemy through the scope of his rifle. Wondering if his foes are talking about the lunacy of American soldiers in Vietnam. Dien Cai Dau, crazy Americans.

With “Red Pagoda,” Komunyakaa talks about a blood stained and wrecked pagoda. And how a symbol of tranquilly is forever defecated. Komunyakaa’s respect for nature and the peace it bestows is echoed in “A Greenness Taller Than Gods.” In the poem, Komunyakaa writes about his lieutenant who follows a map, a map that means nothing in the Vietnam forest.

There is a Buddhist boy at a pagoda in “The Dead at Quang Tri.” Perhaps it is the same pagoda as “Red Pagoda.” Perhaps it is a way for Komunyakaa last reminder of an innocent but necessary death.

“Hanoi Hannah” begins with the iconic American musician, “Ray Charles!” The poem is about a lady known only as Hannah, who spreads Vietnamese propaganda to the American soldiers. Hannah plays the ethnic card and echoes the dissatisfaction amongst African-American soldiers, “Soul Brothers, what you dying for?”

The poems of Dien Cai Dau all have a purpose. It is reckless to say that one poem holds greater impact then another. Each piece of Komunyakaa’s poetry resonates a different experience.

For example, during class on Tuesday Jody (no relation to the Jody in “Combat Pay for Jody”) exclaimed, “I love that poem!” as I did some in-class reading (aka cramming). Jody was referring to the poem, “Sappers.” I had just finished reading the poem and though little of it, except that it was well written. But since there was sincere acclaim for the poem, I decided to re-read “Sappers.”

Komunyakaa’s poem of sappers is one of his closest encounters to death. There is an exclusion for “Thanks,” which Komunyakaa utters gratefulness for a tree that deflected a sniper’s bullet from his flesh.

“Sappers” is an uncanny speedy poem. It is written with the urgency of the Vietnamese sappers who attempt to detonate explosives upon American soldiers by suicide. It is the Vietnamese version of Japan’s famous kamikaze pilots. Komunyakaa portrays “Sappers” romantically as he writes about the Vietnamese who “fling themselves into our arms.”

Although I have previously stated it that it should be deemed “reckless” to choose favorites from Komunyakaa’s Dien Cai Dau, I will do so in the interest of ending this blog entry. The two poems that captured my attention the most were “Dui Boi, Dust of Life” and “Losses.”

The child born to the woman in “Dui Boi, Dust of Life” is “half-broken.” As his father is. The child is a true innocent born into a human hell. The prospect of the child is future-less as his life was an unfair one from conception.

With “Losses,” Komunyakaa imagines himself through the eyes of a former comrade who is confused and disoriented upon readmittance to a world not plagued with war. But even with Komunyakaa’s vivid details there will never be a collective understanding of the ones whose “days are stolen.”

Komunyakaa ends Dien Cai Dau ends with the poem, “Facing It.” Like Michael Herr’s “Breathing Out,” Komunyakaa tries his best to end the Vietnam War chapter of his life. Komunyakaa touches the name of his friend on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington D.C. and immediately remembers the event that killed his friend.

The marble of the memorial will always serve as a reminder of the Americans who lost their lives for a cause no one understands.

Saturday, February 11, 2006

Yusef Komunyakaa

http://www.ibiblio.org/ipa/komunyakaa/bio.html

More interesting material on YK and on Vietnam:

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/g_l/komunyakaa/komunyakaa.htm

and a reading of "Facing It" by another Vietnam vet:

http://www.favoritepoem.org/thevideos/lythgoe.html

and keep looking for yourselves!

aloha, S

Thursday, February 09, 2006

amlit338

The "Collegues" portion of "dispatches" is by far the most poignant, accessible chapter of the book. Accessible in that it tells the story of Herr and his fellow correspondents during their time in Vietname, which is in truth, the only story that Herr, or any other journalist, has the right to tell.

The opening of pt. II begins with a Bob Dylan quote: "Name me someone who's not a parasite, And I'll go out and say a prayer for him."

The concept of parasitism has such a profound presence in the story. Two specifically, that I took notice of, were the parasitism between the war itself and its correspondents, and the parasitism that occurred between the correspondents themselves.

The image of the soldier with the busted lip that gave Herr the "hateful" look stands out in my mind as an instance of the fore-mentioned parasitism. Herr talks of the stares that he had sometimes received from soldiers, stares that "weren't judging me...were'nt reproaching me.... didn't even mind me, not in a personal way. They only hated me." The soldiers in Herr's account are constantly amazed that the journalists don't have to be there, but choose to be. I think that Herr feels a sense of guilt because he's using his freedom, in the midst of all these men who don't have a choice, to put himself smack in the center of the danger. In a way, it communicates a certain degree of the diminished value he has for his life. Whether Herr feels these looks are warranted, he is definitely aware of their legitimacy.

Herr also seems self-conscious of the nature of his work. His work is of a parasitic nature in the sense that his whole being and experience in Vietnam comes courtesy of the killing and murder of men. He talks of the stats and euphemisms constantly being fed to the press and states what the war really came down to was "men hunting men"

It puts him in a weird place, because, as close as he can get to "grunts" or the higher ups, I think he doesn't quite feel a complete affinity toward them. It's as if his own self-consciousness prevents it.

Having said that, this is what makes his relattionships with other journalists so profound; the idea that they are the only ones who truly understand Herr, and what it's like to be a journalist covering the war. In reference to the relationship he shared with his collegues he says; "I doubt... anything else could be as parasitic as that, or as intimate."

Within this simply stated line, Herr conveys the neccessity of having people around who understand, of the neccessity of having people around to share something, whatever it was, with. At the same time, out of this neccessity were framed lasting and meaningful relationships.

For me, this chapter, more than any sums up the book the best. It stands as a reporter's experience in Vietnam. The importance of this statement lies in the specificity of the experience, because as Herr is well aware, especially as explained in the experiences of Vietnam as experienced by the "grunts and conversely the officers, each and every experience is all its own.

Let's play the "Be P.C." game

According to Carlin, the term shell shock originated during the First World War. His argument is that over the last 60 plus years we have transformed the word shell shock into something that sounds a little nicer. It changed into battle fatigue during world war two. As you can see battle fatigue sounds a little more professional. The word shock is missing to make it sound a little less serious and more like a medical term. To quote George Carlin, "Four syllables now. Takes a little longer to say. Doesn't seem to hurt as much. Fatigue is a nicer word than shock."

Then in the 50s, during the Korean War, battle fatigue was changed to "operational exhaustion". The powers that be made the word even longer and less human. Operational exhaustion sounds like what happens when your rifle breaks due to overuse. It's less human, and more "sterile".

Then came the Vietnam War and the term changed again to "post-traumatic stress disorder". And I end this paragraph quoting Carlin yet again because I can't think of anything else on my own. "...thanks to the lies and deceits surrounding that war, I guess it's no surprise that the very same condition was called post-traumatic stress disorder. Still eight syllables, but we've added a hyphen! And the pain is completely buried under jargon."

I think it’s interesting how society changes words and phrases to make them sound a little nicer. Cleaning them up removes the power of the thing, such as shell shock or operational exhaustion or whatever you want to call it. Pretty soon we are going to be calling it post-combat-post-return-premature abnormal psyche condition.

Tracers, and ditches, and spooks, oh my!

So as far as my journey through this book goes...it's been quite the roller coaster of an adventure.

Of course, this far through the book, I've totally ditched any hopes of reading this like a novel (as I ranted about this last time, I figured I should address it here). Actually, im not quite done ranting. I cant help but lament for lack of character development and overall structure. At times I feel like im being given a really gruesome slideshow, sans the...er...slideshow.

Coming to grips with this aspect of the book, though...does make it easier to march on through. Remember how the soldiers were talking about having spurts of insanity, and downright hallucinations? Sometimes I think this book does that to me. My mind kind of went on various excursions through jungles (both natural and urban), and I ended up going in totally different directions than where the book wanted me to go. Doing the report on Vietnam totally helped bring me back to reality - when my mind went off to God knows where , events in the story that I recognized pulled me back to where I had branched off from...and reluctantly, I backtracked the paragraphs where everything went particularly fuzzy.

This whole blog may seem like yet another rant, but i don't mean it to be (DID I REALLY COME TO GRASP THE FACT THAT THE BOOK REFUSES TO BE A NOVEL - hmmm. probably not).

So what the hell do I like? I like the fact that this book isn't fluffy and soft - nor overly patriotic. It's real. vietnam wasn't exactly fighting for the freedom of America, nor was it for the benefit of people who truly needed our help (in no way am i putting those who fought down, though) But all in all the book wraps together (from what I gather), a pretty accurate account of the war from an American's perspective. I may have not been ecstatic to pick up the paperback from time to time, (and quite often found myself asking - did i bookmark the wrong page?) but it's definitely a unique work that I was pleased to have worked my way through. I feel like I not only know the war from a historians point of view, but from a more personal viewpoint.

TRUE DEDICATION

amlit338 Is the most CREATIVE TITLE FOR A POSTING YET!

I managed to sneak in "Zebras" somewhere in my Blog...search for it, it's like "where's waldo" of blogs.

uuuhhmmm.

This time the problem isn't that I don't GET IT. But it's more--I don't like it? I don't fully embrace it? I don't think this is, to quote John le Carre (whoever he is), "The best book I have ever read on men and war in our time."

It's not that I'm completely against the book either. There are some truly insightful moments and some rather poignant lines, but in the end--i guess yeah, I don't get it. Half the time I don't understand the war jargon, "They were both from Hotel Company of the 2nd Battalion, which was dug in along the northern perimeter, but they were taking advantage of the day to visit a friend of theirs, a mortar man with 1/26"--what the heck is Hotel Company? A bunch of men who like hotels? And 2nd Battalion? 2nd Battalion of what? Marines? Army? Calvary? Zebras? I can make conjectures at what a mortar man is but what is it that he does 1/26th of?

(Okay...i'm not THAT military illiterate...I'm pretty sure Hotel Company is the term form H-Company, 2nd Battalion is PROBABLY referring to a Marine Battalion, and 1/26 is really something like 1st Battalion 26th regiment)

but still...the point is, I don't really NEED to know that the Hotel boys were going to visit the mortar men. I find myself skimming through most of the technical blabbering until I get to another human-realization-epiphany-war-is-hell-moment.

SHIFTING FOCUS:

I was talking to Spencer earlier this week about how my OWN life is quite the Vietnam in itself. I had two missed doctor's appointments, the first because I went to the building and found out my doctor moved, the second because I thought it was a week earlier than it actually was—wasting a total of $26 dollars on cabs/buses. I then found out my landlords decided NOT to let me get a cat which crushed my spirits tragically. AND to top it off...THE SEAHAWKS WERE ROBBED IN THE SUPERBOWL!!!

I mean, come on, my life SUCKS!

Oh, wait...maybe that's just me bitching.

And reading this book makes me realize that yes, I am just bitching--in fact, my life is pretty WONDERFUL compared to the grunts who had to worry about their hoo-ha's being blown off. In fact, my life has been pretty sugar-coated, handed to me, my toughest decision is what shoes to wear, simple.

This book has put my own life into a rather unsettling perspective. Reading/watching/hearing about Vietnam always makes me realize how difficult I DON'T actually have it. Kind of makes me want to shut up and join the army--except not really, because i have no balls. But still. Bravo to those who survived. A bigger bravo to those who didn't. Vietnam was some heavy shit that I could have never gone through, and if anything, Herr does get that message across loud and clear.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

I've been in the trenches, bitch, and I've seen the grim reaper slapping me around like the whore that I am

Maybe it's the drugs. His, not mine. Maybe his ramblic style appeals to that lost generation of burnout hippies turned blue-balled-collar workers. Maybe they felt the "normal" journalists' just couldn't give them a voice. Maybe it was exactly his confusing style that made them say, "DAMNIT, HE WRITES LIKE I THINK: Like he's batshit insane!"

Or is it because he was there so long and therefore his opinion matters. Maybe because he was there with the men in the field for years, writing, laughing, shooting, singing, dancing, crying, peeing, drinking, and maybe even loving, that gave him his "street cred." Whatever it the reason, I still don't agree that it is all that and a bag of juicy fruit. I honestly felt Hunter S. Thompson's coverage of a motorcycle race in "Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas" was a better piece of journalism. Sure, his articles had NOTHING to do with the motorcycle race (or VietNam), but he showed what we all want to see: The American Dream.

And as for this whole thing about not wanting the book to interfere with your Joey viewing, I must say that I disagree. I have been desensitized to violence, so most of the stuff in this book doesn't affect me. It's too impersonal of a book for me to be affected by it anyway. I don't really get to know the characters that are dying. The character I think I connected with the most was the one who was trying to get on the plane to go home. He kept waiting out there, scared, laying in the trench, watching his plane to safety fly away over and over again. I was affected more by his FEAR than by any other violence in the book. Helicopter filled with corpses? Meh, seen it, done it.

I don't think it will hurt your pretty little heads to read about a little bit of horror. I think living through horror is one of the best things that can happen to a person. To a point. I know these people, made into killing machines, were made the worse by it, but in my personal experiences, I love life more now than most of the people around me. People that have it better off than me get depressed and sad and all whiney over petty things in their lives. Sure, I have my down days, but after living through many experiences that I didn't know whether I would live, and having friends that didn't live through them, I can appreciate life on a level that not many people can. Once death flops its bulging shade over your head, steals your friends, and makes it clear to you that you can go at any minute, it changes your view on life. You can find the oddest things funny, including death. You can be politically incorrect and not care. You can dance in an elevator as it takes you down 17 floors. You can sing "L is for the way you look at me," as you walk down the hallway with your sister. You can play air guitar in a restaurant that is considered "Fine Dining" because it strikes you as something that would be enjoyable. You can even make long rants on a class blog that have nothing to do with the reading... Well, sort of... That'll do...

To sum it all up: What doesn't kill you will only make you happy.

"How Much Time You Got?"

Herr achieves nirvana because he was not your typical reporter during the Vietnam War. Herr himself did not see himself as a reporter either—“no, a writer.” But he indeed was a reporter, a journalist, and a historian.

Although Herr does use literary references to connect with his pompous audience, it is his dialogue with colleagues that makes Dispatches appealing. Herr’s acquaintances are the elites of journalism. They report on the war not because it has become part of their lives.

Herr’s three closest acquaintances are photographers Sean Flynn, Dana Stone, and Tim Page. There is something quirky about photographers, particularly war photographers, as they seem invulnerable. Sometimes a photograph is so amazing and destructive that you have to wonder how the photographer made it through alive.

It is through dialogue with his colleagues that Herr’s Dispatches becomes profoundly authentic. Because writing is never a one-person process. You write because you want to tell the world about your experiences. And you cannot have a worldly experience without having close human bonds.

Of all his mates, only Herr made it through the Vietnam War. Flynn and Stone have disappeared and Page is physically incapacitated. It may be that Herr’s chapter on “Colleagues” was a work of love and remembrance to comrades.

Discussing Dispatches is much like discussing art. No two people can view a piece of “art” the same way. But I do agree with Ian’s (aka SampleThis) comment on this blog that distancing oneself from Herr’s book “takes a stance on no stance.” Turning away after you dipped your hand in the cookie jar is suspect.

The base at Khe Sanh was the most provoking reason why the Vietnam War should never have happened. How else does one describe a base held in hostile enemy territory that is a landmark one day and just another piece of jungle the next? All the manpower, all the anxieties that each solider suffered…all for nothing—nothing at all.

Khe Sanh was also where Herr begins a lengthy character dialogue with soldiers Day Tripper and Mayhew. The greatest thing about Mayhew and Day Tripper were that they were the best of comrades, during a time when ethnicity was constantly a battle in their own country.

The friendship of Day Tripper and Mayhew proved that ethnicity discrimination in the United States made no sense. There is a famous photo by Larry Burrows that showed an African-American solider, Jeremiah Purdie, reaching out to his injured white comrade. Purdie is mud-drenched with a blood stained head wrap while his comrade is slouched in the mud.

Ethnic barriers did not exist for American soldiers in the Vietnam War. Soon after the war, there were none domestically as well. If the Vietnam War had any benefits for the American people, it was the destruction of ethnic barriers.

The destruction of Saigon was left to the Vietnamese, after all.

Tuesday, February 07, 2006

First essay--topics

February 6, 2006

Prof. Susan M. Schultz

First Essay

5 pages: due February 21

Write on one of the following topics. If you would like to write on something else, you need to clear it with me first. Whatever you choose to do, you need to make a strong case for your argument, using evidence, detail, and passion. In other words, write in a voice distinctly your own, while making certain to speak directly to your audience (think of your audience as me and as your classmates). Be sure to maintain a focus appropriate to a 5-page paper (not The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire!).

1. We’ve read Ginsberg, O’Connor, and Herr against the backdrop of American history in the 1950s and 1960s. But we’ve only touched the tip of the iceberg. Hunt down some of the (related) references in one of the texts we’ve read and explore the ways in which the author uses them in his or her work. In what ways is a knowledge of these references crucial to understanding the text you’ve chosen? Use on-line resources, including Al Filreis’s 1950s page, and the library.

2. Do a formal analysis of one of the writers. Why must Ginsberg write a catalogue, rather than use more traditional forms? What does the short story form do for O’Connor that the longer form might not? Why does Herr eschew traditional narrative, in favor of a more episodic structure? Consider the content of their work, and how the forms they use help them deal with that content.

3. (semi-creative essay) Write a dialogue between two of the authors we've read so far, on a subject of interest to them both. If you do this one, keep the chitchat to a minimum, and do the work of an essay, as well as use the form creatively. Assume that the authors have read each other's work carefully, can cite pages and quotations, and that they are engaged in a purposeful argument over a literary and/or historical topic.

on Ian's comment

Ian--I took that comment toward the end of class as being an expression of how profoundly affected the speaker was by what she sees and reads, so that not wanting to read the book is not an act that denies sympathy, but oddly discloses it. Even so, I take your framing of the question to be a good one: to what extent can we ethically turn away from other people's suffering (or the evil they do)? If we do turn away, are we responsible for what we do not see, to change Herr's wording? Look to Herr for his answers, then tackle the question, using your own experiences as a guide.

aloha, Susan

Dead Dead DEAD Little girl... lol

Sunday, February 05, 2006

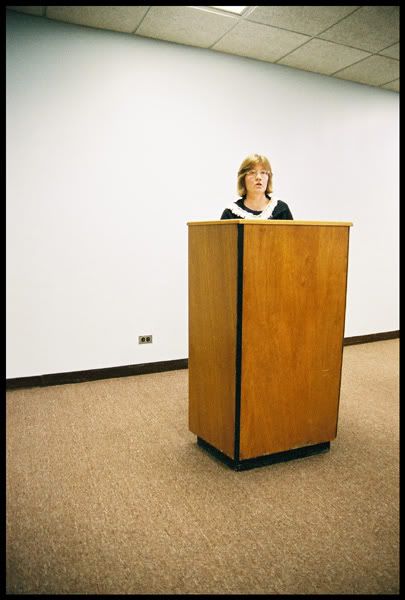

Professor Schultz's First English Department Colloquium.

agent orange

I tried to provide a link to agent orange (the exfoliant) but it wouldn't take.

But what I really want to know is why, when I call up awful words like "napalm" and "agent orange," I get sites for BANDS. Yuck.

sms

Heads (and ears) up for Tuesday

"Trouble Every Day," by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, 1966

http://www.zmag.org/songs/Trouble%20Every%20Day.htm

Watts Riots (subject of the song):

see the Wikipedia for facts

Pres. Lyndon Johnson's response:

http://multied.com/documents/LBJwatts.html

California Prop 14 (one of the triggers for the riots):

http://en.wkipedia.org/wiki/Proposition_14

Lyrics for Jimi Hendrix's songs, "Are You Experienced?" and "Foxey Lady" can be found at

http://www.rocklibrary.net

Lyrics for Jimi Hendrix's "Machine Gun":

http://www.sing365.com/music/lyric.nsf/MACHINE-GUN-lyrics

Lyrics for the Beatles' "Magical Mystery Tour" and the rest of the album:

http://members.tripod.com/~taz4158/magical.html

Some images from Vietnam by Larry Burrows, a journalist who died in Laos:

http://www.life.com/Life/burrows/vietnam.html

Famous photo of the execution of a Vietcong soldier:

http://www.themodelminority.com/misc/images/execution.jpg

Napalm photo of little girl:

http://www.p10k.net/Images/Vietnam_girl_napalm.jpg

Napalm

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napalm

Agent Orange:

And can someone please explain to me why when I call up words like "napalm" and "agent orange" I get BANDS???? What kind of sick is that?

aloha, sms

Saturday, February 04, 2006

another death to report

Another important figure from the 1960s has died, Betty Friedan. Look to the New York Times (nytimes.com) for her obituary.

sms

important movie

from my friend, Esther Figueroa. If you don't know who Emmett Till was, look him up.

if you haven't had the chance to see "the untold story of emmett louis till"

it is at the academy today and tomorrow. please go and see it. it is one of

the most important and powerful stories ever told.

love fig

Friday, February 03, 2006

Dispatches O' Houlihan

Standard journalism seems to be concerned with bird's eye view facts, so that "the comfortable" can make vicarious judgement calls from the comfortability/misery or their sofas and wive/husbandss who don't want to fuck them anymore.

In my opinion(and yes, I'm well aware this has become a rant bigger than the story so ill try to sum it up in a bit) the narrative form of Herr's journalism gives us a grim/hilarious/insane/etc. look into the story beneath the story, and the one beneath that one, and the one nestled even deeper, within the jungles of Vietnam or the minds of the men/boys who experienced it firsthand, or a journalist who was slowly becoming something new.

In the end, fictionalized journalism allows its reader the same freedoms any other "unbiased" work would do; they allow them to draw their own conclusions, and to ascribe whatever meaning they choose to. One type of journalism isn't better than the other, in fact they appeal to different parts of us, but I think that in the same way mythology is an equally important part of our history and our present, as "factual" history is, so it is here.

Unbiased? fuck no. But equally as valid as obejective journalism is? I'd have to say "yeah, sure, why not."

Thursday, February 02, 2006

Dese Patches are Scattered!

i don't feel as if there is any real flow from one exerpt to the next (but then again SHOULD there be?) if this were a novel, then i would hope events would be given more coherance, but since its not (IS IT?), i've come to the conclusion that i will just read one memory to the next, accepting each as its own entity. even when i try to do this, though...i still have some trouble accepting how jumbled things are. when i sit down with someone at lunch, and they tell me a short story of an experience, i can't express any more how irksome it is if they get all A.D.D. with everything and things just don't add up appropriately. granted herr has an awesome experience to share, and i enjoy hearing all the bits and pieces, but if things just lined up better i'd be a lot happier of a reader.

here's another rant: what's the deal with the italics? if everything's a memory...why accent another more than it's predecessor, or perhaps the next in line? im still trying to figure out what to do with those (i learned in a previous class that font, and style are used as tools to tell the reader how the piece should be read - correct me if im wrong susan ;) but when i come across these suckers in this book im like "whoa, what the heck?!"

so wait...is there ANYTHING i like? truth be told : yes. i love this guy's ability to take his memories and just totally blow it up in the words so that the reader feels like they are there. dialog is realistic, too. the way it's on print is how i imagine the soldiers talking. his use of description and dialog are like tasty spices in an otherwise bland sauce (forgive the analogy - i had indian food recently). the writing style itself isn't difficult to read (hmmm just hard to follow / flow....hmmm....and maybe an army - terms - glossary would be good.

all in all, i'm not done reading it yet so we'll see where this goes.

last thought....how do i pronounce lz....i mean is that an "l" or a 1? is it a code term or is it a word? see a glossary would help.

War is hell, and funny

I wanted to comment a little bit on the humor in the book Dispatches. I know this is supposed to be a very serious book, and it is, but when you come across something that makes you chuckle it just jumps out off the page. Kind of ironic that in a subject like war, that seems like the epitome of seriousness, comedy can still prevail, if for only a few sentences.

Take page 34 for example. "There was a famous story, some reporters asked a door gunner, "How can you shoot women and children?" and he'd answered, "It's easy, you just don't lead 'em so much." Now I'm not saying that shooting women and children is a hilarious thing but I find it amusing that the soldier was so far gone that he answered the question literally.

On page 28 the narrator describes a Marine walking around in the jungle because his group was tired of waiting for action and that "He'd come out to see if he could draw a little fire...I didn't want to bother him while he was working." This passage is a good example of how war can make men ridiculous and I hope I'm not the only one who chuckled at this passage.

The last thing I found amusing was on page 67 when the narrator is describing a scene in which a soldier was going to skin a dead Vietnamese person. The lieutenant comes over and yells at them saying reports were around and finished with, "There's a time and place for everything." Once again, not laughing at skinning dead people but just the fact that it seems like the lieutenant is going to come over there to let them have it but instead just basically says "Wait a while would ya?".

War is Crazy!

I met a person once who was in the war in Iraq and was sent back with a purple heart. Everytime I saw him he was drunk or on drugs. I even saw him do ice in front of me. When I asked him why he did those things he said it was because he was afraid to sleep. If he slept he would dream about his time in Iraq and he didn't want to dream. I never judged him to doing drugs or the way that he was because I know that what he went through is something that I would never be able to understand. He disappeared one day and I never saw him again. Sometimes I still wonder what he's doing now.

When I was reading Dispatches I also thought that this reporter had some courage to go to Vietnam and risk his life just for a story. I don't think that I would be able to do such a thing. I also think that anyone that goes to war has courage. I know some other people that are being deployed to Iraq in a couple of months and when I talk to them I can tell that they are getting nervous and scared. Although I want to say something to comfort them I really don't know whas to say, but war is just CRAZY and I hate it.

A note on genre

_Dispatches_ is not a novel, but a collection of essays written originally for _Esquire_ magazine (of all places). But it will be interesting to think about the ways in which Herr uses the devices of a fiction writer. Be sure to ask Prof. Heberle questions today!

aloha, Susan

Dispatching Your Patient's Patience

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

“There’s nothing so embarrassing as when things go wrong in a war.”

When Michael Herr, a journalist, steps into Vietnam he is fulfilling a perverse desire to understand the war. This is a ludicrous idea, as war is hell. There is no understanding, not even those who orchestrate the war.

Herr can only tell the tales. And most of his tales are small sporadic ones; so disorganized one has to wonder if each happened in its own lifetime.

When Herr writes about the ten-year-old Vietnamese boy who has lost his mind, the reader becomes well aware that while American soldiers are having it rough, it is the Vietnamese civilians who are suffering the most.

When Herr write about the young Marine who laughs at him after accidentally kicking Herr’s nose. Or about how some of the CIA’s spooks have disappeared in their own private agendas, you begin to see how human discourse takes a steady tumble in war.

By page 85, a reader gets the feeling that Herr himself has no clue as to what he observes. This in unison makes Herr the prized journalist, an observer who makes no assumptions.

And like Herr, the reader is both terrified and flabbergasted at war’s capacities to the disillusion of men.

There is no way to explain war. When the President (in a generic sense) speaks about how the war is progressing, she/he speaks as though she/he understands it.

Herr was in the Vietnam War. He wrote a novel for about it. And it is so bloody obvious that Herr to this day does not understand why anything happened.

When the President tries to have discourse on war to the media it is always about progress. There’s nothing so embarrassing as admitting to a wrongful war.

As a side note: During Tuesday’s class, A.J.’s observations of O’Connor’s Good Country People was in my opinion, the best dissection of O’Connor’s literature yet. Quite frankly A.J. had the best (so far) supporting evidence for his analysis. I support “C.S.I: Literature.”